Gottlieb Blaess - Missionary to the Māori

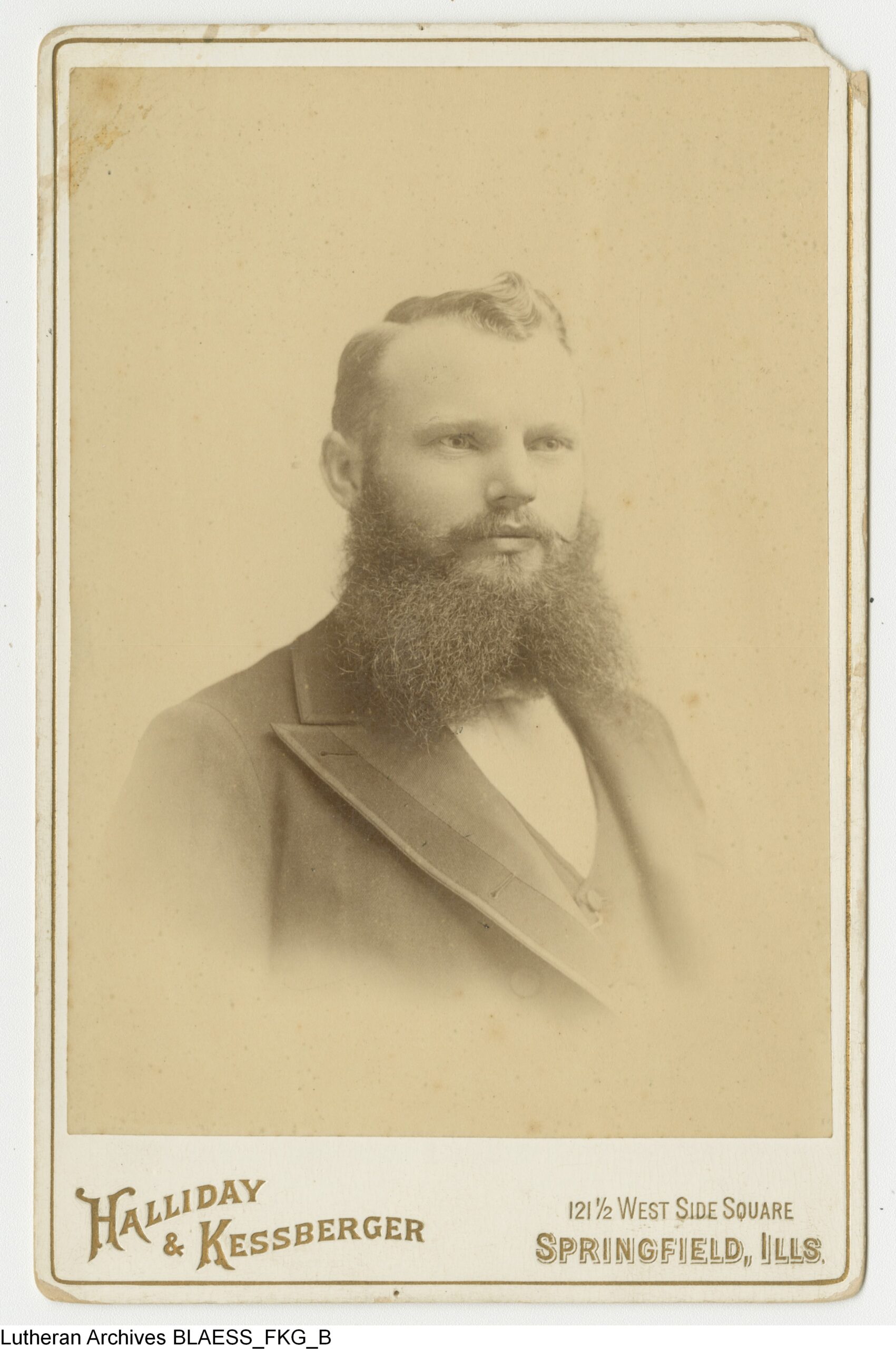

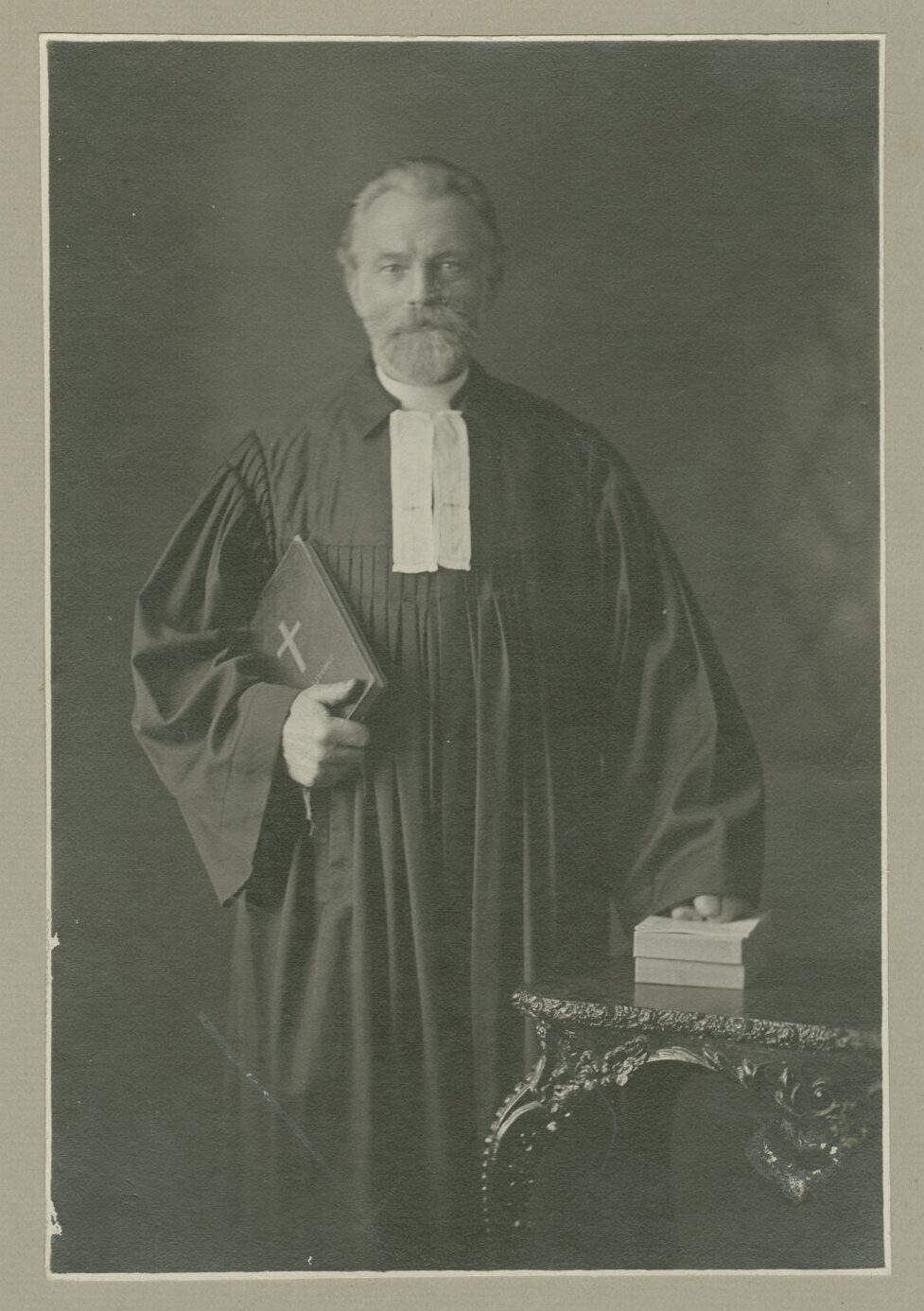

Friedrich Karl Gottlieb Blaess (1864-1928)

Missionary in New Zealand, 1893-1906

When 29-year-old theological student Gottlieb Blaess returned from his Christmas holidays in the winter of 1893, he found a very serious letter waiting for him. It was from Pastor Wohling of the Hermannsburg Free Church in Germany, and extended him a call to serve as missionary in New Zealand.

Born and bred in the Harz Mountains in Germany, where he had spent his youth working as a gardener, Blaess had begun his theological training in the mission schools of Berlin and Hermannsburg. His uneasiness with the teachings of the State Church in Prussia prompted him to finish his theological studies in the USA, where he enjoyed a free education at Concordia Theological Seminary in Springfield Illinois.

Blaess did not take the task of a prospective missionary lightly. He wrote in his reply to Pastor Wohling on 8 January 1893 that “a call of such high importance and responsibility … demands a man of great ability and surpassing gifts, strong faith, great self-sacrificing courage and solemn integrity, and great self-denial”, and that making this decision would require “earnest examination, fervent prayer, and the advice of experienced men.” In fact, he was so unsure of his own suitability for the role that he referred the final decision to his professors, whom he also felt conscience-bound to involve in the decision of where he served, after the support he had received from their synod. In the meantime, he would pray daily and earnestly “that I may recognise [God’s] holy will and, if it is His will, that he may grant me joyfulness and strength in the acceptance and carrying out of this call.”

On the advice of his lecturers, Blaess accepted the call. After graduating in May the same year, he travelled to Germany for his ordination, then sailed on the Hohenstaufen to Australia and onward to the New Zealand North Island, where he served as a missionary to the Maori people in the Taranaki region for 13 years.

Records from Mission in Taranaki

Gottlieb Blaess left a treasure trove of records behind him, filling four boxes on the Personal Papers shelves at Lutheran Archives. While some of these pertain to his later ministry as an ELCA pastor in Australia, there is a wealth of earlier material documenting his time as a missionary in New Zealand.

Blaess kept a diary between 1899 and 1916, and a copybook of correspondence and reports from 1902 to 1912, both of which overlapped with the latter part of his ministry in New Zealand and provide insights into his daily activities, as well as the increasing difficulties and concerns of his task. Blaess’s diaries were the primary source used to write the detailed biography of his life and mission work included in the Blaess family history. For a detailed account of Gottlieb Blaess’s life and work on the mission stations at Normanby and Pungarehu, see Eric R. Blaess (ed.), Under the Southern Skies: The Story of Missionary Gottlieb Blaess in New Zealand and Australia (Lutheran Publishing House, 1992).

Blaess also preserved original correspondence from his time in New Zealand. This included correspondence with Pastor W. Wohling back in Germany, as well as letters from fellow Lutheran pastors and missionaries serving in NZ during the period, such as W. F. Schwarz in Upper Moutere and C. C. W. Meyer in Marton. One English letter from William Leonard Williams, the Anglican Bishop of Waiapu, (dated Napier, 11 March 1896), shows that Blaess kept abreast of the mission efforts of other denominations in New Zealand too. Williams informs him that “the King Country is visited by Archdeacon Clarke … under whom two Maori clergymen are working steadily in the district, apparently to good effect. … The Wesleyans also have a Maori missionary working in the district”. The letter also hints at a certain level of cooperation between denominations as they served in different regions, informing Blaess that the people in Taranaki “seem to be in the greatest need just now”, and recommending him to get in touch with a clergyman in Whanganui who “might be able to make some practical suggestions”. (Indeed, keeping abreast of developments seems to have been important to Blaess, as many of the 19th century foreign periodicals and LCMS synod reports held at Lutheran Archives came to us through his collection.)

Another document, undated (though marked ‘1905’ by a previous archivist), lists reasons “for and against” the continuation of the Maori mission. Lutheran mission in the Taranki region had long been an uphill battle. A history of war and violence between the Maori and European settlers, and cruelties experienced at the hands of settlers and colonial authorities, had turned many Maori away from the Christian religion, in addition to the opposition of two influential Maori chiefs, Te Whiti and Tohu. Even among those people who were receptive to the Christian faith, Blaess ran into other difficulties, such as a preference for sending their children to English-speaking public schools where the opportunities were greater. The mission was finally closed in 1906, and Blaess transitioned to work as a parish pastor of the ELSA synod in Australia, where he retired in 1923 due to ill health, and passed away in 1928.

Despite the mission’s closure, Blaess’ work in New Zealand left one important legacy. When Blaess asked a young Maori man called Hamuere Te Punga to help him translate Martin Luther’s small catechism, the work had a transformational spiritual effect. Te Punga was baptised as a Christian in 1906 and decided to dedicate his life to the pastoral ministry. On Blaess’s recommendation, Te Punga went to study at Concordia Theological Seminary in Springfield, Illinois, where he met and married his wife Lydia Gose. He returned to New Zealand as the first Maori Lutheran pastor, serving first as missionary among the Maori in Lower Hutt, and then as a parish pastor based in Halcombe from 1921-1951.